Tapak

OCaml web frameworks work well, but they miss opportunities to leverage OCaml’s unique strengths and twists.

For example, both Opium and Dream use traditional string-based routing systems. Compare them with Haskell’s Servant, which uses advanced type-level programming to provide type-safe routing and automatic API generation.

Another example is Rust’s Warp, which uses Filter systems. These leverage Rust’s powerful type and trait system to provide composable and type-safe routing and automatic conversion from types to HTTP responses.

Both depend on Lwt for their asynchronous programming model— the older asynchronous I/O runtime. This is understandable since they were written before OCaml 5.

OCaml 5 introduces algebraic effects, this means we can express asynchronous I/O without any monads at all. EIO is a new I/O runtime for OCaml that uses algebraic effects and direct-style concurrency. We don’t need monad transformers, and the composability of monads is no longer a concern. Why not leverage that instead?

I mean, instead of using Lwt’s monadic style:

(** int64 -> Request.t -> Response.t Lwt.t *)

let handler id request =

let* user = Database.get_user_by_id id in

let* posts = Database.get_posts_by_user user in

Lwt.return (Response.of_json posts)

We can write it in direct style with EIO:

(** int64 -> Request.t -> Response.t *)

let handler id request =

let user = Database.get_user_by_id id in

let posts = Database.get_posts_by_user user in

Response.of_json posts

The monadic style is powerful, but it doesn’t compose well with other abstractions. For example, if you have validation

abstractions, you will end up with a mess of monad transformers. In practice, you will often need to validate

data based on the state you have in the database layer. So string -> bool validation functions are not enough; you need

string -> bool Lwt.t functions. Composing these with Lwt becomes cumbersome quickly.

The error handling in Lwt is also not ideal. We can’t use language constructs like try...with to catch errors in Lwt computations.

So I decided to explore building my own web framework built upon EIO and providing more modern features I found lacking in existing frameworks. Let me introduce you to Tapak.

The Problem with Traditional Routing

Traditional routing APIs require you to manually extract and parse parameters:

Dream.get "/users/:id/posts/:slug" (fun request ->

let user_id = Dream.param request "id" |> Int64.of_string in

let slug = Dream.param request "slug" in

handler user_id slug request)

Problems with this approach:

- Parameters come as strings, requiring manual parsing

- Type mismatches only caught at runtime

- It’s easy to make typos in parameter names

- No compile-time guarantees

Here’s how Tapak solves this:

(* Tapak: type-safe parameter extraction *)

get (s "users" / int64 / s "posts" / str) @-> fun user_id slug req ->

handler user_id slug req

(* user_id is already int64! slug is already string! *)

The magic? The compiler knows user_id is int64 and slug is string. If you try to use them incorrectly,

you get a compile error, not a runtime crash.

Let me show you how it works.

Type-Safe Routing with GADTs

What if we could encode the route structure directly in the type system, so the compiler can:

- Validate that handlers receive the correct parameter types

- Generate URLs from the same route definitions

- Catch routing errors at compile time, not runtime

Since we wanted to match routes and extract parameters in a type-safe way, we need a way to represent path patterns with types. This is where GADTs come in. They allow us to specify the exact types of parameters they return, enabling us to encode rich type-level information.

Let’s define a GADT to represent path patterns:

type (_, _) path =

| Nil : ('a, 'a) path

| Literal : string * ('a, 'b) path -> ('a, 'b) path

| Int64 : ('a, 'b) path -> (int64 -> 'a, 'b) path

| String : ('a, 'b) path -> (string -> 'a, 'b) path

| Method : Piaf.Method.t * ('a, 'b) path -> ('a, 'b) path

(* ... more constructors *)

Here’s a breakdown of how we express path patterns with types:

Two type parameters:

('a, 'b) path'a: The accumulated function type (builds up as we add parameters)'b: The final return type

Type threading: Each constructor modifies the first type parameter to “accumulate” extracted values

The end goal is to have a type like (int64 -> string -> Request.t -> Response.t, Response.t) path for a route like

/users/:id/posts/:slug, which means the handler must accept an int64, a string, and a Request.t, and return a Response.t.

Let’s define functions to describe the path patterns:

let int64 = Int64 Nil

(* int64 : (int64 -> 'a, 'a) path *)

let str = String Nil

(* str : (string -> 'a, 'a) path *)

let s literal = Literal (literal, Nil)

(* s : string -> ('a, 'a) path *)

(** more path functions *)

We also need a way to compose paths to achieve (int64 -> string -> 'a, 'a) path. For that, we define the / operator:

let rec ( / ) : type a b c. (a, c) path -> (c, b) path -> (a, b) path =

fun left right ->

match left with

| Nil -> right

| Literal (lit, rest) -> Literal (lit, rest / right)

| Int64 rest -> Int64 (rest / right)

| String rest -> String (rest / right)

(* ... *)

The / operator composes paths by recursively threading the right side into the left side’s rest parameter.

This is how we chain multiple segments together.

Let’s see how this works in practice:

get (s "users" / int64) @-> user_handler

Type evolution:

s "users"→('a, 'a) path(no parameters extracted)/ int64→(int64 -> 'a, 'a) path(adds int64 parameter)get→ Wraps in Method GET@-> user_handler→ Requires handler of typeint64 -> Request.t -> Response.t

Pattern Matching and Extraction

Since we have the path patterns encoded in types, we need a way to evaluate them at runtime to match incoming requests.

As we match the path segments, we also need to extract parameters and build up the handler function call. Fortunately, the type system will guide us to ensure we evaluate them correctly.

let rec match_pattern : type a b.

(a, b) path -> string list -> Request.t -> a -> b option

=

fun pattern segments request k ->

match pattern, segments with

| Nil, [] -> Some k

| Literal (expected, rest), seg :: segs when String.equal expected seg ->

match_pattern rest segs request k

| Int64 rest, seg :: segs ->

(match parse_int64 seg with

| Some n -> match_pattern rest segs request (k n) (* Apply extracted value to continuation *)

| None -> None)

| String rest, seg :: segs -> match_pattern rest segs request (k seg)

(* ... *)

k is a partially applied handler function. As we extract parameters from the URL, we progressively apply them to k,

building up the final function call.

For get (s "users" / int64) @-> fun id req -> ...:

- Match

"users"→ continue with samek - Parse

"123"asint64→ apply tok, gettingk 123L - Reach

Nil→ returnSome (k 123L request), which evaluates the handler

Request Guards

I’ve been working on web applications since my early career, and one common pattern I’ve found is validating requests— like requiring certain headers, authentication, or specific content types. This is usually handled outside the routing API.

Certainly, we can add middleware for that. But we can’t express it in the type system, leading to potential mismatches. I’ve made mistakes a few times where I forgot to attach the correct authentication middleware to a route. It’s also not particularly clear just by looking at the handler definition. It’s much clearer if the handler is declared as follows:

let admin_handler user req = ...

The user parameter explicitly tells me this handler requires an authenticated user. The routing system should

only call this handler if the request is authenticated. I found this pattern really useful.

So I decided to add Request Guards to Tapak’s routing system. Here’s how it looks:

let ( >=> ) : type a b g. g Request_guard.t -> (a, b) path -> (g -> a, b) path =

fun guard pattern -> Guard (guard, pattern)

Usage example:

get (user_guard >=> s "users" / int64) @-> fun user id req ->

(* user : User.t, id : int64, req : Request.t *)

Response.of_string ~body:(Printf.sprintf "User %s viewing %Ld" user.name id) `OK

Guards add validated data extraction before path matching. The type (g -> a, b) path shows that the guard’s result (g)

becomes the first parameter.

Composing multiple guards:

Request guards are normal functions, so we can compose them naturally. Tapak provides combinators to help with that.

Their definition is straightforward:

type error = ..

type 'a t = Request.t -> ('a, error) result

Here’s an example combinator to combine two guards. Both must succeed, and their results are combined into a tuple.

(* &&& combinator combines two guards, both must succeed *)

let authenticated_json = Request_guard.(user_guard &&& json_body) in

post (authenticated_json >=> s "api" / s "posts") @-> fun (user, json_data) req ->

(* user: User.t, json_data: Json.t, req: Request.t *)

create_post user json_data

URL Generation

Another use-case of routing systems is generating URLs. Django and Rails provide helpers to generate it based on route names.

We can use the same GADT path patterns to generate URLs in a type-safe way. Just like our favorite

OCaml sprintf function, we can define a sprintf function that takes a path pattern.

let rec sprintf' : type a. (a, string) path -> string -> a =

fun pattern acc ->

match pattern with

| Nil -> acc

| Literal (s, rest) -> sprintf' rest (acc ^ "/" ^ s)

| Int64 rest -> fun n -> sprintf' rest (acc ^ "/" ^ Int64.to_string n)

| String rest -> fun s -> sprintf' rest (acc ^ "/" ^ s)

(* ... *)

(* Usage *)

let user_path = s "users" / int64

let url = sprintf user_path 42L (* "/users/42" *)

There you go, type-safe URL generation using the same path patterns.

Routing Scope

Most web frameworks provide a way to group routes under a common prefix or apply middleware. This is usually called “scopes” or “namespaces,” and it’s useful for organizing routes, applying common middleware, or versioning APIs.

Tapak provides routing scopes as well:

App.(

routes

~not_found

[ get (s "") @-> home_handler

; get (s "users" / int64) @-> user_handler

; scope

~middlewares:[api_auth_middleware]

(s "api")

[ get (s "version") @-> api_version_handler

; scope

~middlewares:

[ require_email_confirmed_middleware

]

(s "users")

[ get (s "") @-> api_users_handler

; get int64 @-> api_detail_user_handler

; post int64 @-> api_update_user_handler

]

]

]

()

Want to try it out?

You can install Tapak using Opam by pinning the GitHub repository:

# Pin from GitHub

opam pin add tapak https://github.com/syaiful6/tapak.git

# Install dependencies

opam install tapak --deps-only

Or you can use Nix Flakes. Add Tapak as a flake input in your flake.nix, and you know the rest, right?

You use nix btw.

{

inputs = {

tapak.url = "github:syaiful6/tapak";

# Or specify a branch:

# tapak.url = "github:syaiful6/tapak/main";

};

outputs = { self, tapak, ... }: {

# Use tapak in your development environment or package build

};

}

Cons of GADT-Based Routing

To be honest, GADT-based routing is not without trade-offs. It is more complex and requires a DSL, which means you need to learn new concepts and familiarize yourself with the API.

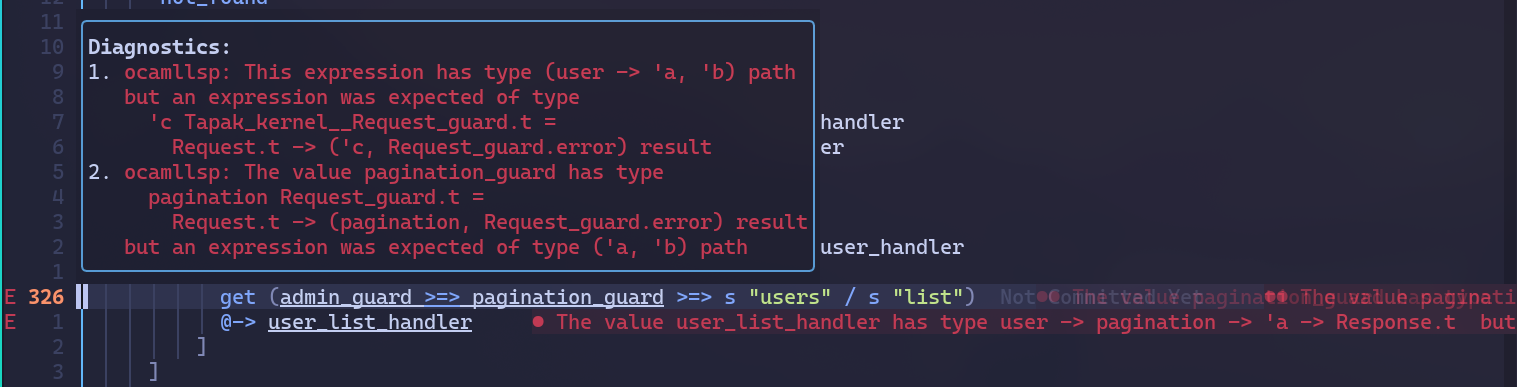

The error messages can be quite cryptic and intimidating for newcomers. Consider this code:

get (admin_guard >=> pagination_guard >=> s "users" / s "list") @-> user_list_handler

What’s wrong with it? The error message might look like this:

See? The error messages can be overwhelming. They basically say the >=> operator was applied to the wrong arguments—

it needs to be applied to a path pattern, but here it was applied to another guard instead. The fix is simple: just add

parentheses to make the grouping explicit:

get (admin_guard >=> (pagination_guard >=> s "users" / s "list")) @-> user_list_handler

But I believe the benefits outweigh the costs.

Since OCaml has ppx, we can use it to generate the GADT routes from a more familiar string-based syntax. I tried using Django-style route definitions with ppx, and it works quite well.

I focused on building a solid foundation with the GADT-based routing system first. Once that’s stable, I can explore building ppx-based route definitions to lower the barrier to entry.

Static File Serving

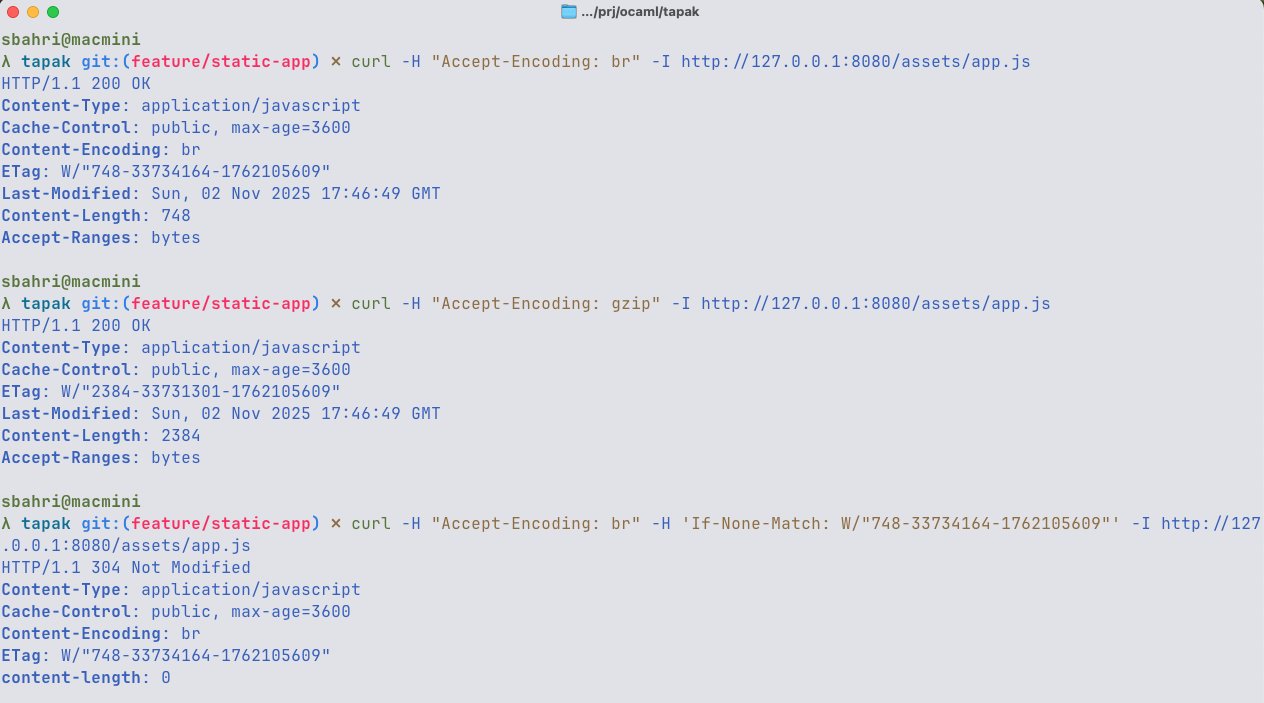

Another feature I found lacking in OCaml web frameworks is robust static file serving. Both Opium and Dream provide static file serving, but they simply serve files from a directory with limited support for advanced optimizations, such as range requests, conditional requests, caching headers, pre-compressed files with content encoding negotiation, and other optimizations that are important for serving static files efficiently.

They also lack flexibility. What if I want to serve files from embedded resources, from a CDN, or generate files on the fly?

This is why I decided to implement a more robust static file serving solution in Tapak.

The API looks like this:

let cwd = Eio.Stdenv.cwd env in

let public_dir = Eio.Path.(cwd / "examples" / "static-files" / "public") in

let fs_backend = Static.filesystem ~follow:false public_dir in

let static_config =

{ Static.default_config with

max_age = `Seconds 3600 (* Cache for 1 hour *)

; use_weak_etags = true

; serve_hidden_files = false

; follow_symlinks = false

; index_files = [ "index.html"; "index.htm" ]

}

in

let app =

App.(

routes

[ get (s "static" / splat) @-> Static.serve fs_backend ~config:static_config () ]

()

)

The fs_backend is a static file backend that serves files from the filesystem. It can be replaced with other backends

by implementing Tapak’s Static STORAGE module signature. For example, I can implement an embedded file backend generated

by OCaml-crunch.

Ongoing Features: Real-Time

Modern web applications have evolved beyond the traditional request-response model. Users now expect instant updates, collaborative features, live data streams, and more.

Think about it—if you wanted to build a web application that can analyze chess games with coaches or friends in real-time, this feature is a must-have. This is why WebSockets and Server-Sent Events (SSE) have become essential primitives in modern web frameworks.

Tapak already supports SSE, and WebSockets are available through Piaf.

Node.js’s socket.io and Elixir’s Phoenix Channels are popular solutions for building real-time web applications. Their client libraries make it easy to connect to the server and handle real-time events.

If we can implement their protocols in OCaml, we can leverage their existing clients, which would be a huge win. Supporting a custom protocol would mean building both client and server libraries, which is significantly more work.

This is an ongoing project—I’m exploring building the Phoenix Channels protocol in OCaml, which is more feature-rich compared to Socket.IO. It has presence tracking, which is useful for showing online users, typing indicators, etc.

Sunday project: Cooking up a real-time communications API in #OCaml. 🐫 pic.twitter.com/BnC9Tx40hu

— Syaiful Bahri (@kicauipul) November 16, 2025

Conclusion

This is what I’ve built so far with Tapak. It’s still a work in progress and an experiment on what an OCaml web framework could look like when built on modern OCaml with everything I’ve learned so far. But I’m excited about the possibilities!

The GADT-based routing system shows that type safety and ergonomics don’t have to be at odds. By encoding routes in the type system, we get both compile-time guarantees and a clean, composable API.

The framework is still experimental, so feedback and contributions are very welcome! If you try it out or have questions, feel free to open an issue on GitHub.